The Five Sign Language Rights

The 5 Rights Created through a Domestic Research Survey by the Project to Push the Creation of a Sign Language Law

The Japanese Federation of the Deaf (JFD) received assistance from the Nippon Foundation in 2010 and started the project to push to creation of a sign language law, where they ran domestic and international surveys. In the international survey, they looked at countries and regions which had established sign language laws, and the results are summarized in “The Status of Legal Recognition of Sign Language in Countries Around the World”. In contrast, the domestic survey, which formed the foundation of the “five sign language rights” covered in this section, was run with the intention to make clear what deaf people’s experiences have been when it comes to discrimination against sign language.

Extracting data from surveys conducted in the past, individual hearings of deaf persons, back catalogues and related materials from the JFD’s newspaper bulletin Japanese News for the Deaf, and other documents and material related to deaf and hearing impaired persons, we counted 1,214 cases of discrimination against sign language, and separated them into the following five different categories as a result of our analysis.

Using this classification pattern, the JFD has developed them into the five sign language rights, and devised a public awareness schema used in booklets and other materials in the effort to propel forward the establishment of a sign language law. Below, we explain the five rights, corresponding each of them with the kinds of symbolic discrimination that they match.

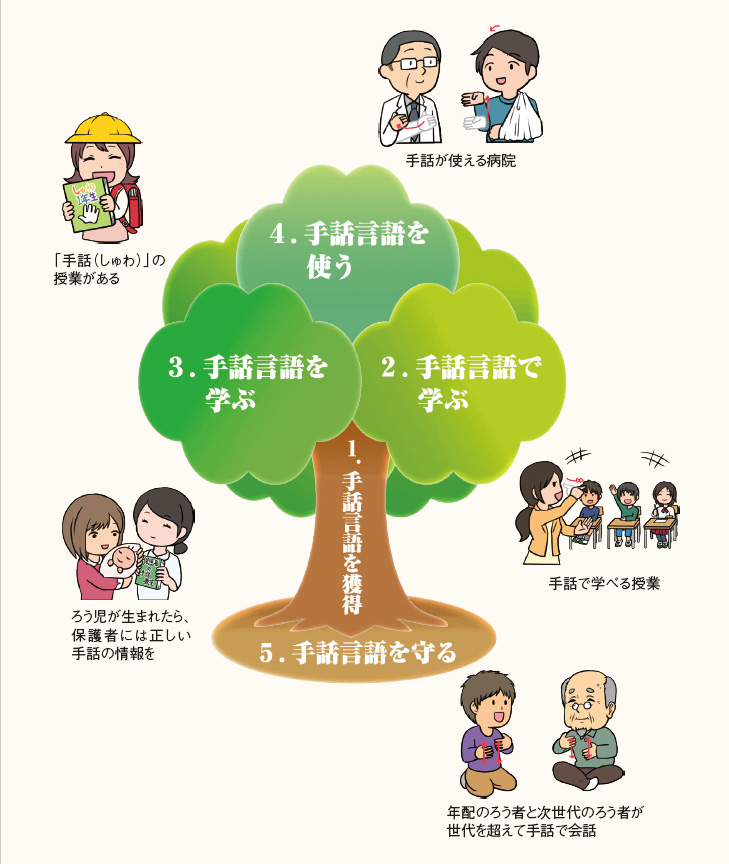

Picture: The Tree of the Five Rights of Sign Language

Source: The Japanese Federation of the Deaf “Let’s GO with Sign Language! Towards a Rich Society with Sign – Moving Towards the Establishment of a Sign Language Law” (November 2016)

Acquiring Sign Language: The Right to Acquire Sign Language as a Native Language from Infancy

It’s normally the case that native languages are transferred from parents to children in the household, but because 90% of parents of deaf children don’t know sign language, there are very few examples of sign language being passed from parents to children. As a result, there are few chances for children and parents to get in touch with sign language, and children end up being unable to participate in households that use oral communication. This leads to an extremely large number of deaf adults who feel discriminated against with regard to native language acquisition. In order for deaf children to acquire sign language, we must guarantee an environment where families and people close to families can receive an adequate amount of information about sign language and that the sign language acquisition of children and people around them is well supported. Since the adequate guarantee of acquiring and learning sign language is a major prerequisite towards the following rights of “learning in sign language,” “learning about sign language,” and “using sign language,” this right of “acquiring sign language” belongs in the trunk of the “tree of rights,” which illustrates the five sign language rights.

Learning in Sign Language: The Right to Learn from Teachers who Use Sign Language and Sign Language Interpreters

Even if deaf children acquire sign language as their native language, we can’t declare that their right to learn is being met if their educational environment provides insufficient opportunities for learning through sign language. There are cases in special auditory support schools (deaf schools), where large amounts of deaf children gather, in which children are unable to learn directly from teachers in sign language. This includes cases such as teachers who don’t know sign language conducting classes, and arithmetic classes which consist solely of children reading word problems. There are also cases where deaf children are mixed in with hearing children all throughout primary education without the placement of sign language interpreters, which results in the obstruction of scholarly ability and the simplification of teachable material. Across the educational spectrum, including higher education, we must guarantee the right to learn for deaf people.

Learning about Sign Language: The Right to Learn about and Deepen Understanding of the Language One’s Own People Use (Sign Language), Like How Japanese People Learn about Japanese in School

In Japanese schools, children can deepen one’s knowledge of Japanese through the Japanese studies (kokugo) curriculum. In other words, children are guaranteed the chance to increase their ability to use Japanese and deepen their knowledge of the language through classes where they about its grammatical structure and are exposed to Japanese literature. On the other hand, there no exists no such curriculum in which deaf children can deepen their knowledge of the sign language that they use. There are only few cases in special education where this subject is taken up. Our surveys report cases where deaf education teachers don’t have knowledge about sign language and there are no teachings in general about sign language grammar, among other examples. This reveals a deep need for a school curriculum where children systematically learn about sign language grammar and for classes where children have chances to enjoy creative works in sign language.

Using Sign Language: The Right to Use Sign Language in Quotidian Circumstances, Like Using Sign Language among Peers or Having Interpretation Services in Various Daily Scenarios

When looking at circumstances outside of school life, daily life does not provide an environment where sign can be used in a variety of circumstances. There are numerous examples that illustrate various circumstances like being unable to consent to urgently needed surgery due to doctors not knowing sign language, not being able to grasp the opinions of bosses or coworkers in work settings where there is no sign language support, or meetings in the household where even if one asks for sign language interpretation those requests are denied. Through guaranteeing an environment where deaf persons and hearing people who know sign language can use sign language, parents of deaf children can rest easy knowing that there is a wealth of options for children to acquire sign language as their native language. We can illustrate this right as the connection between the foliage at the top of the tree and the tree’s trunk in the “tree of rights.”

Protecting Sign Language: The Right to Preserve, Promulgate, Research, and Deepen Understanding of Sign Language

The “tree of rights,” with its foliage and branches, illustrates rights which pertain to the individual use of sign language. However, the tree needs a vast amount of soil on which to grow, so we can see that the “right to protect sign language” corresponds with that soil. In other words, the right to protect sign language is a social right that does not lie in the territory of individuals. It resolves problems remaining in society that pertain to misunderstandings, prejudices, and lack of recognition towards sign language and promulgates proper understanding and enlightenment about it. There are reports of examples where, among other cases, people have scorned the use of one’s sign language, and students have been told by teachers that because the material of college classes is quite abstract it would be impossible to use interpreters. Meanwhile, people have also pointed out the lack of colleges in which one can research sign language, illustrating a dearth of public sign language resources. The current effort to establish sign language regulations and laws is one way of promoting the preservation, promulgation, and research of sign language, in addition to increasing understanding of sign language.

Conclusion

By looking at cases of discrimination towards sign language, we understand that the violation of the five rights intersect and interact with each other, giving rise to a more complicated and diverse set of problematic conditions.